From Evergreen Investing: October 2023

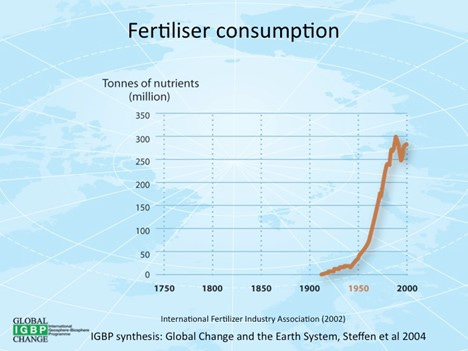

New ways of thinking catapulted fertilizer use in the mid-20th century, triggering the first Green Revolution. It’s credited with alleviating world hunger and saving countless lives.

That was a true paradigm shift.

In the February issue, I made the case that feeding 8 billion people today would lead to great opportunities. This month I circle back to this arena and show how striving to reach that goal sustainably will favour particular agrifood subsectors.

But first, I’ll detail this sector’s progress over millennia so you can better understand how and at what pace we arrived where we are today, and why the future is so bullish.

Let’s start with a look at this chart of fertilizer consumption.

How did the planet go from relatively limited to explosive use? This true paradigm shift, like those Gwen fleshed out last month, embodied new ways of thinking and doing that became widely adopted and created tremendous wealth for those involved.

Before we look at where this paradigm shift is heading next, let’s look back at how agriculture evolved.

According to a team led by archaeobotanist (a new term for me) Amy Bogaard from the University of Oxford, the use of manure as fertilizer dates back 8,000 years. That turned on its head the previous estimate of 2,000 to 3,000 years. Odds are, like so many discoveries throughout history, it was a fortuitous accident. Bogaard’s team believes early farmers likely noticed better crop growth where dung accumulated in areas where animals gathered. That discovery was a paradigm shift because, for subsistence farmers, any notable yield improvement would have been very desirable to replicate.

Babylonians, Egyptians, Romans and early Germans eventually began using minerals to boost farm yields, but manure remained the prevalent fertilizer for several thousand more years. Then, in the 19th century, German chemist Justus von Leibig pioneered organic and biological chemistry. His “Theory of Mineral Nutrients” laid the groundwork for agricultural chemistry, explaining that three chemical elements, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, are indispensable to plant growth. These three remain the fundamental crop nutrients today.

Leibig is known as the “Father of the Fertilizer Industry” for developing the first nitrogen-based fertilizer. Others, like Nobel laureates Carl Bosch and Fritz Haber, built on Leibig’s work: the Haber process uses molecular nitrogen and methane to generate ammonia both economically and sustainably. The eponymous Ostwald process (using ammonia produced by the Haber process) generates nitric acid commercially. This “piggybacking” by researchers on previous work led to economically viable production of both nitric acid and ammonia as the central ingredients of most chemical fertilizers in the early 20th century.

These were all lesser paradigm shifts. Despite all this progress, the biggest leap was still to come.

The Green Revolution was triggered in the mid-20th century when advancements in fertilizers along with the development of high-yielding varieties of wheat and rice meant large increases in production. New technologies were first deployed in developed nations, then spread quickly across the globe into the late 20th century. This was a slow start to the green revolution, which then got an unexpected boost from suddenly available crucial infrastructure and morphed into a big paradigm shift.

In the aftermath of World War II, many large U.S. facilities near natural gas pipelines could now produce nitrogen for agriculture rather than munitions. This repurposing of large infrastructure unleashed a massive ability to rebuild food supplies in both the U.S. and Europe. Advances in crop production like hybrids, crop nutrition guidelines, new high-performance equipment, and the discovery of huge potash deposits all came together around the late 1940s to trigger the modern fertilizer era.

Now have a second look at the chart above and you’ll see that’s when fertilizer use exploded. Massive adoption and widespread use is credited with saving billions of lives from starvation. Today more than half the world’s food production depends on mineral fertilizers.

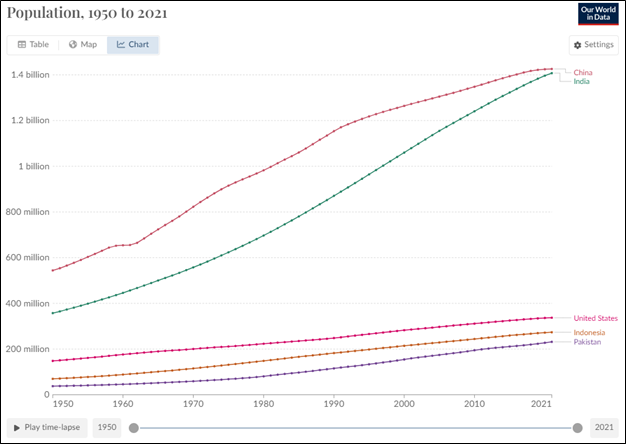

Now let’s talk about the investment angles here. China’s modernization (and population growth, along with India’s) in recent decades helped drive the impressive resource bull markets of the 1970s and the 2000s.

Source: Our World in Data; United Nations, World Population Prospects (2022)

Decades of underinvestment in production of all kinds of resources clashed with surging demand, causing prices to soar. Agricultural nutrients were no exception. Chemical fertilizer use in China multiplied from 8.84 million tons in 1978 to 52.51 million tons in 2020. Today, China is the largest user of chemical fertilizers globally.

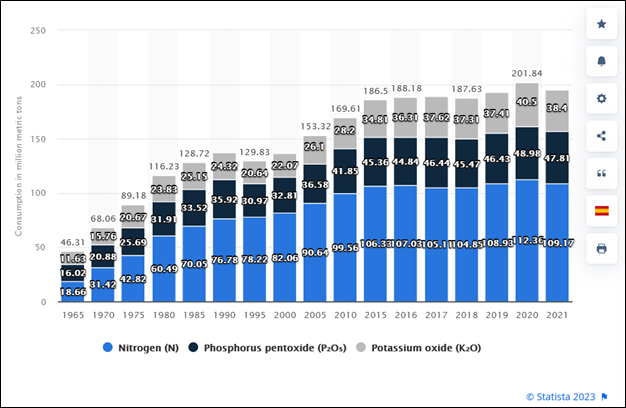

We can see China’s impact in this next chart. Between 1965 and 1985 world fertilizer consumption nearly tripled from 46.31 to 128.72 million metric tons. It then moved sideways as production capacity caught up. But China’s growth kicked in again in the 2000s. Global fertilizer consumption grew another 45% between 2000 and 2016.

Global Consumption of Agricultural Fertilizer (1965-2021) by Nutrient

In the February issue I detailed how the biggest recent challenges for the agrifood industry include the Russia-Ukraine war, post-COVID inflation, supply chain issues, and deglobalization.

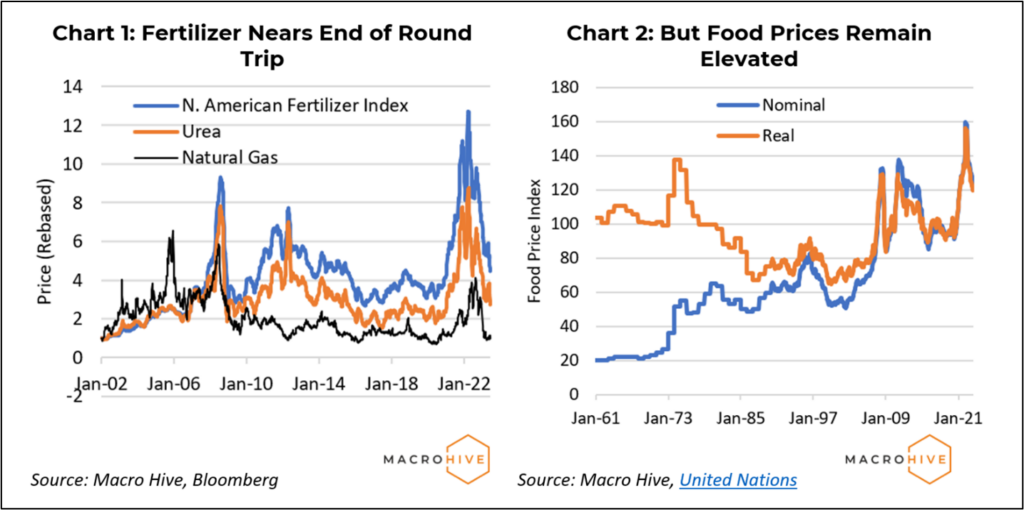

Since then, fertilizer prices and natural gas – a key input – have fallen back considerably. And yet, food prices have remained stubbornly high. Why? Farmers face labour shortages and rising costs. China and Pakistan have been hit with floods that hurt rice yields. The US has suffered dry weather denting soybean yields. Now you have the perfect storm (pardon the pun) for high food prices.

The bad news is ongoing high inflation is likely to mean elevated food prices. But as farmers continue to receive a high price for their produce, they will want to boost output. The simplest and quickest way in most cases is to increase fertilizer use, especially since fertilizer prices have moderated.

And there’s another exciting development to watch: “green ammonia”. That’s ammonia produced from 100% renewable and carbon-free energy sources, which can be used just like regular ammonia to make agricultural fertilizers. At the University of Minnesota, Michael Reese leads a farm research project. Their studies demonstrate that using “green ammonia” as fertilizer, fuel and heat could lead to a 90% drop in carbon emissions from corn and small grain crop farming.

But “green ammonia” has another emerging use case. Thanks to its chemical structure ammonia is ideal to store electricity and power ships. The Oxford Institute of Energy Studies concluded in 2020 that liquid ammonia was perfectly suited for large-scale, long-term energy storage. Several countries like the U.K., the Netherlands, Japan and Australia are aiming to use “green ammonia” to store and export their surplus clean energy supplies. Developments like these are exactly the types of opportunities we seek to leverage at Evergreen Investing.

Today most ammonia is produced using the Haber-Bosch process using natural gas. The problem is that it releases nearly 2 tons of CO2 for each ton of ammonia. But innovation is changing things. One U.S.-based one ammonia producer is leading the charge.

This content is available thanks to subscriber support.

To subscribe to the full newsletter, subscribe to Evergreen Investing here.