From Evergreen Investing: August 2023

The green transition is a paradigm shift. This matters to us at Evergreen Investing because paradigm shifts create major investment opportunities and new ways of operating that replace longstanding setups.

This shift is changing how the world moves, builds, eats, lives, and works. And big change like this requires big support, in particular from governments that mandate and then support the transition. Big changes also require new inputs, whether that’s materials or energy or technology or people.

Put it together and the green transition sits at the intersection of politics, money, and resources. It is happening because of political mandates; it demands immense investment; and it requires all kinds of new materials, energies, and technologies.

And this complex transition is happening in a world that is pivoting to deglobalization as it recovers from two big financial setbacks and navigates big new fractures in international relations.

This month, we want to explain how deglobalization is impacting the green transition. Long story short: it’s enhancing the investment opportunity for anyone who understands that politics and trade go hand in hand.

What & Why of Deglobalization

Deglobalization is a move towards lessening dependence and integration between nations and businesses around the world.

Like most major shifts, deglobalization brings pros and cons. On the one hand, limiting one’s trading partners is likely to lead to higher costs and complicate access to certain resources. On the other hand, it can enhance supply chain reliability while spurring innovation, substitution, and investment opportunities.

For most of history, the infrastructure to move information and goods was too slow to support a truly global economy. But technology caught up after World War II and, over the next 80 years,

most of the planet enjoyed increasing globalization, a growing interdependence of businesses and economies.

But the global machine it created had to stretch long distances, bridge significant political and social differences, and absorb endless financial challenges. That was a tall order and the machine was not up to the task.

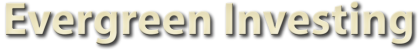

It’s difficult to pinpoint the exact beginnings but in hindsight the 2008 financial crisis was the genesis for deglobalization. The UK’s Brexit, increasingly strained US-China relations, COVID-19, and lately the Russia-Ukraine war have successively intensified this trend. World trade, as a share of GDP, seems to have peaked right around the financial crisis, with a downward bias ever since.

The financial crisis made everyone suddenly and acutely aware that major problems in one economy are contagious, spreading through a globalized economy like wildfire. Policymakers and politicians soon became critical of globalization. Free trade developed a tainted image of low wage countries absorbing jobs and intellectual property.

Around the same time, it became increasingly clear that the resources needed for the green transition – metals, energy sources, processing and refining capacity, specific manufacturing infrastructure – are not spread evenly around the world.

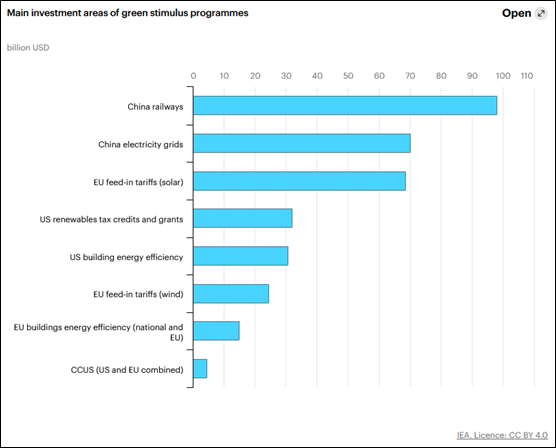

The deep recession triggered by the financial crisis aligned with the 15th Conference of the Parties to the 2009 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP15) in Copenhagen. COP15 made it clear that governments needed to start spending big money if they were going to live up to green promises.

This alignment helped governments realize they could address three problems at the same time if the financial stimulus they provided to fight recession was also green and domestically focused.

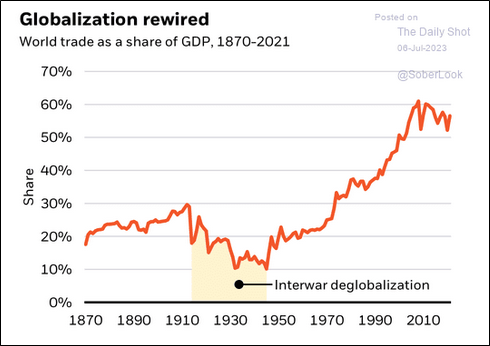

Countries around the world have designed green transition spending to maximize domestic benefit ever since. There are endless examples. Rail infrastructure in China got the largest single boost of US$100 billion, a huge investment that created jobs and longterm national benefit while advancing green goals. The European Economic Recovery Plan included support for energy efficiency that also created EU jobs and built infrastructure that acted as stimulus during construction and created enduring green efficiency and innovation.

America led its charge with an early stimulus package that included a significant clean energy component.

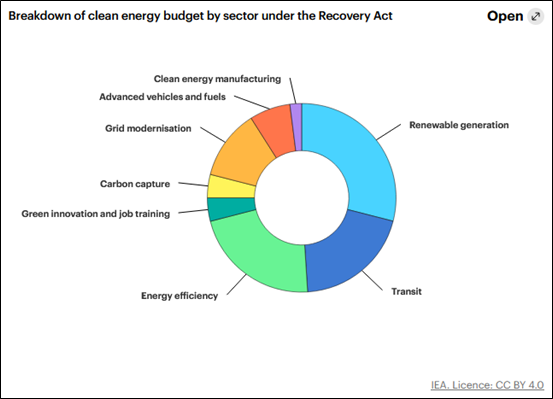

Then the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act allocated about US$90 billion across clean energy sectors, including grid modernization (12%), carbon capture, and mass transit (20%), while energy efficiency and renewable generation received a combined 51%.

As detailed in last month’s issue, the Paris Climate agreement came next and accelerated emissions caps, renewable energy buildout, and clean energy technologies. Governments were very financially supportive, especially with interest rates at historic lows.

Subscribe to Evergreen Investing

COVID-19 was the next shock and caused everyone to seriously question their dependence on others for supply chain essentials like medical, food, and energy supplies. We made it through, but at a very high financial cost. Governments announced billions of dollars in stimulus programs that soon turned into trillions. Again, a lot of that money found a “green” home.

If governments went green in responding to the financial crisis, they doubled down responding to COVID. Global populations accepted that stimulus was necessary to save industry and reignite economic activity in the wake of widespread and lengthy shutdowns. After all, energy and infrastructure spending typically benefits everyone, even if indirectly.

“Green stimulus” became widespread, from fiscal measures (tax and spending actions) to aid economic growth in the near term while encouraging environmental improvement in the longer term to numerous programs in energy efficiency, clean energy technologies, electrical grid upgrades, and transport electrification, most of which have decades and hundreds of billions of spending remaining. And emphasizing the green transition was an easy sell.

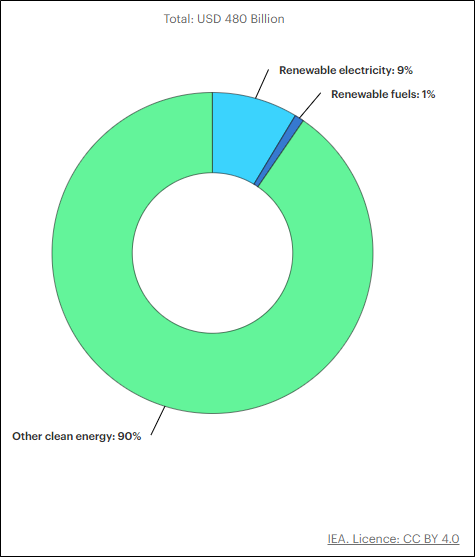

Emerging from the 2008 financial crisis brought about a notable increase in CO2 emissions, with 2010 registering the largest increase ever. Policymakers were determined to avoid a repeat. By October 2021, just 18 months into the pandemic, the global government clean energy stimulus had reached nearly half a trillion dollars worldwide.

The headlines proclaiming these moves shout Green first, but Domestic Benefit follows close after. The move to put one’s own citizens and needs first comes in three forms:

- Energy security

- Resource nationalism

- Onshoring, Nearshoring, and Friendshoring

Energy Security

Russia’s war on Ukraine in early 2022 sent shockwaves into Europe, especially on the energy front. Numerous European nations – Germany in particular – were highly dependent on Russia for natural gas. But sanctions suddenly meant much of Russian energy was off limits or dramatically reduced. Energy prices spiked, with utility bills up five to ten times for many consumers. Europeans immediately sought to accelerate alternative energy from domestic suppliers or “allies.”

Renewable energy from solar and wind saw a sharp acceleration and are set to double in the next five years for their dual green and domestic credentials. Global renewable capacity is forecast to grow by 2400 gigawatts between 2022 and 2027, equal to China’s entire current power capacity. That’s 30% more than had been forecast just 18 months ago. Green was the first reason to build renewables, but the fact that renewable power does not depend on resources that must often be imported is now a strong second reason. Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the IEA, said the world will add as much renewable power in the next five years as it did in the previous twenty, driven partly by a focus on energy security in a deglobalizing world.

Russia’s Ukraine invasion had another big green energy impact: nuclear power quickly regained favor in many countries. The International Energy Agency (IEA) had already said that nuclear energy output needed to double within 20 years to meet global net-zero targets. And it’s also a power source that any nation can, with foresight and cash, develop for itself. The US government started a strategic uranium stockpile and is backing new US uranium production. France makes more nuclear power than it needs, selling its excess to neighbours. Even oil power Saudi Arabia has a detailed nuclear power development plan and is negotiating with China and the US about where to source uranium.

Because it brings these big current forces together – it is a green necessity, requires government will and money (both ample right now), and relies on a strategic commodity – we think the uranium/nuclear outlook is very compelling. Our pick, the Sprott Uranium Miners ETF (NYSE:URNM), is a diversified fund focused on companies that produce, own, or explore for uranium. We think these forces bearing down on a uranium sector that doesn’t produce enough pounds to meet rising demand will create a significant uranium bull market in the next few years.

Resource Nationalism

Resource nationalism surfaces when countries decide to prioritize their resources for domestic use first. Shortages or even the risk of shortages, whether medical, energy, food, or fertilizers, are simply too much of a political hot potato. They’d rather risk offending a trading partner than their own voting citizens. Even before the Russia-Ukraine war, large agricultural producers had begun limiting their exports in the wake of COVID-19 induced shortages. War in Eastern Europe amplified these trends.

In the February issue of Evergreen Investing, we made the case for a rising agrifood sector, thanks to population growth, climate change, and deglobalization’s push for local food sources and self-reliance. Policy and industry-led changes are making the shift to green agriculture. So we added the VanEck Agribusiness ETF (NYSE:MOO) to the portfolio. MOO is a fund of companies that broadly cover the agriculture, animal health, fertilizers, seeds and grains, farm equipment, and livestock susbsectors. As deglobalization advances, these businesses will thrive thanks to increasing demand for sustainable and local food sources.

When it comes to the inputs for green development, the story is much the same. China currently represents 81% of global solar panel production. The country is responsible for 63% of the world’s rare earth mining, 85% of its processing, and even 92% of rare earth magnet production. Yet China has a history of limiting rare earth element access as retaliation for other contentious issues, by raising export quotas, export taxes, or even outright bans.

Risk consultancy firm Verisk Maplecroft’s resource nationalism index tells us that 33% of the 198 countries studied increased control over their resources in the past six years. Mexico is a good example. Since becoming President in 2018, Mexican President Obrador has upped state control of the energy sector from 40% to 56%. Last year, he nationalized the lithium industry. (With the rapid proliferation of electric vehicles, lithium for batteries has soared in value). Chile then followed Mexico, nationalizing its own lithium reserves this past April.

Control over the natural resources needed for the green transition is a key concept in global relations today and thus is driving governments to support domestic production. That means it is also a key driver in investment dollars. Think lithium, uranium, nickel, and silver – all markets where end users are already scrambling to secure local, or at least friendly, sources of supply. Scrambling for supply creates high prices.

Onshoring, Nearshoring, and Friendshoring

Onshoring is the reverse of offshoring: it brings business inside national borders. Nearshoring is establishing business activities in a local region or nearby country. Friendshoring is manufacturing and sourcing from countries considered to be geopolitical allies.

Onshoring and nearshoring may add labour costs, but they can also help reduce transport times and expenses. The US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) boasts $374 billion of green incentives, grants, and subsidies, many of which apply only to American-made products and services. American Clean Power, a renewable energy lobby group, estimates the expectation alone of the IRA prompted $40 billion of investments and almost 7,000 new jobs in late 2022. The EU offered its own Green Deal Industrial Plan, determined not to be left behind. Comprising $240 billion in loans and $21 billion in grants, it subsidizes green businesses, facilitating job training, faster permitting for clean tech projects, and easier access to critical minerals for member countries.

Friendshoring and nearshoring are forcing businesses to reexamine who they deal with. One great example is the potential for the US to develop manufacturing in Mexico. Mexican labour costs mean it’s about 30-40% cheaper to produce goods there versus China. Mexico’s membership in the North American Free Trade Agreement erases tariffs. Physical connections with rail and highways are in place. The Ford Motor company just boosted its Mexican investments by $760 million and plans to triple EV production capacity.

More broadly, since no country can produce all the resources and goods it needs domestically, the deglobalizing world is focusing on trading blocs. The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) is a key development. This group has coalesced in recent years for trade and its members have been actively developing alternative payments systems and trade agreements in their own currencies, seeking ways to sidestep the US dollar and western political influence. This trend kicked into high gear when the US and Western allies froze Russian assets in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine war.

Today, more than 40 nations are interested in joining the BRICS bloc.

As investors, it’s important to not only understand what green materials or technologies are needed but where the users want them to originate. For example, EV manufacturers are seeking better control their supply chains, which is prompting several to invest directly in mining companies. With governments offering big incentives to keep business domestic or friendly, they are investing domestically or within a “friendly” group of countries. There are many moves like these – grounded in the green transition but happening in a deglobalizing world – and, to invest ahead, you must understand where lines are being drawn on the deglobalized, resource nationalism-first world.

Deglobalization will continue to have significant implications for all the arenas we cover here at Evergreen Investing. Government policy is driving change and adoption through new rules, subsidies, and investment and tax credits. We will keep bringing you research and guidance on the most sound opportunities out there.

This content is available thanks to subscriber support.

To subscribe to the full newsletter, subscribe to Evergreen Investing here.